Artist Statement about Rocks and Tapes

May 2020, Brooklyn

At age 21, I suffered a near-fatal bike wreck that left me flat on my back on a slab of asphalt in the middle of the desert. I was bleeding to death in the blistering heat with a crushed spleen. I was alone and, more dangerously, losing consciousness fast. Somehow I got myself home where, after passing out and being awakened by our family dog licking my face, I was finally able to call for help. I eventually recovered but the experience left me with a seven- inch scar and a lasting sensitivity to the proximity of cataclysmic disaster. No matter what I make, themes of threat and aftermath are deeply embedded in my aesthetic.

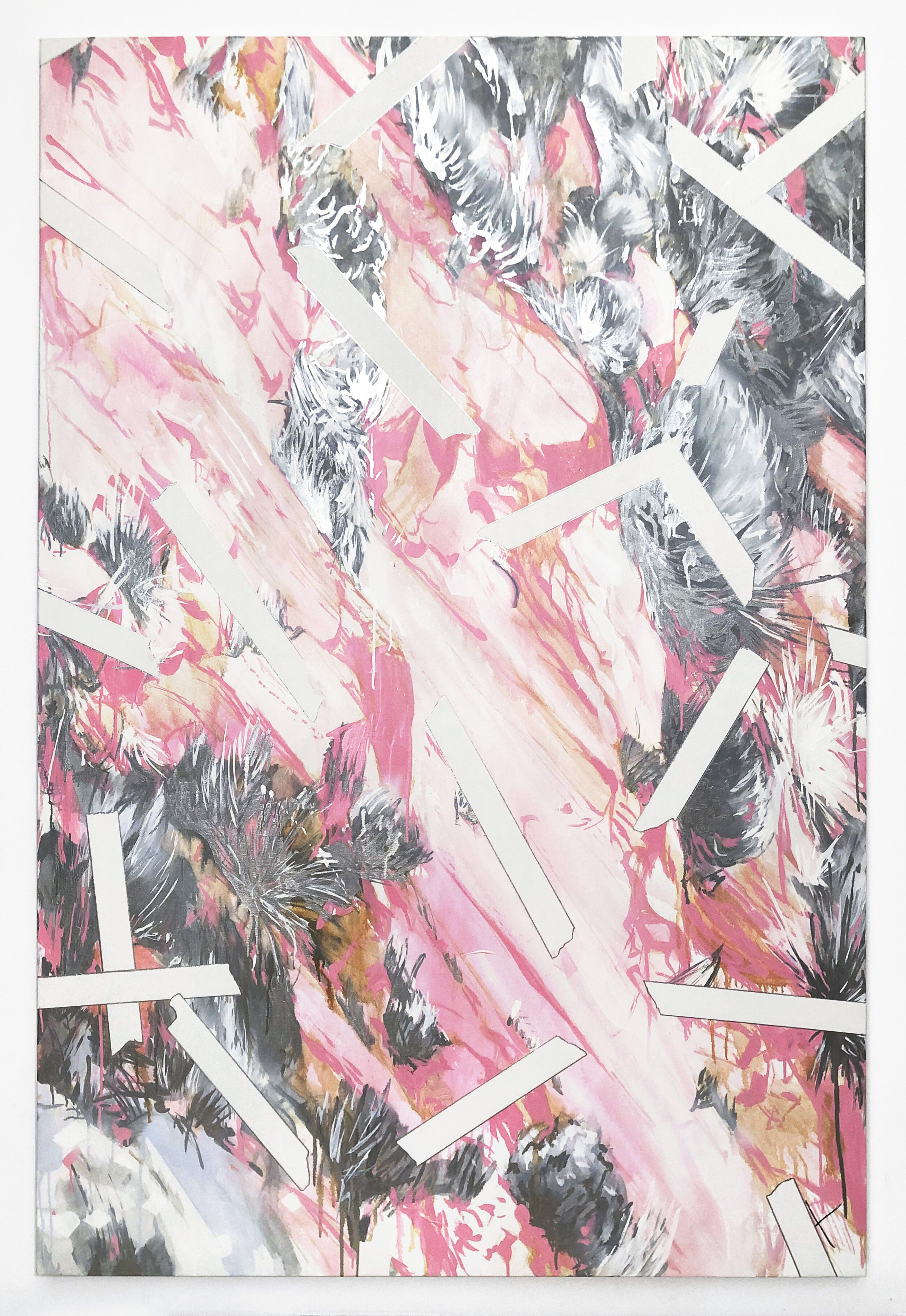

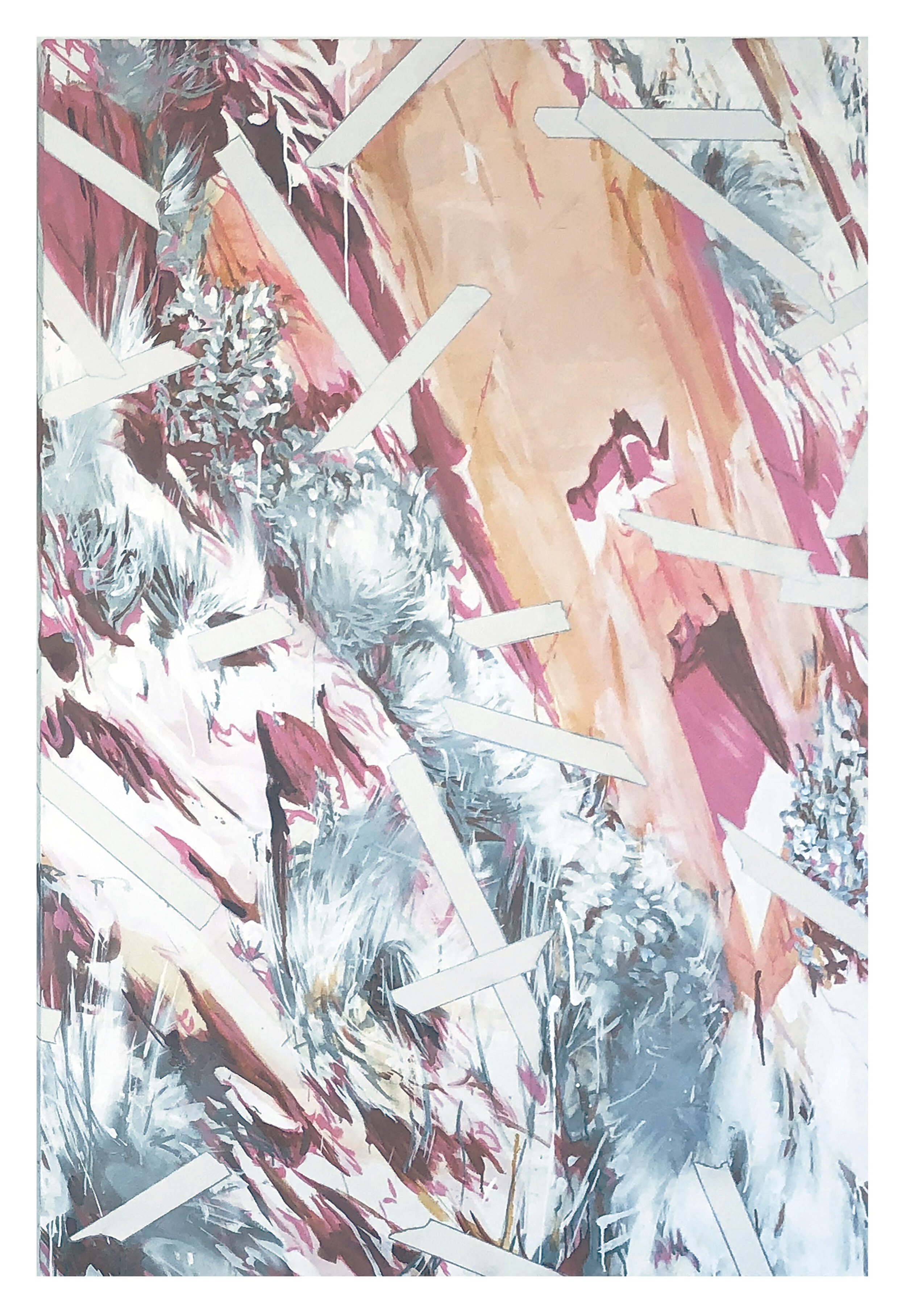

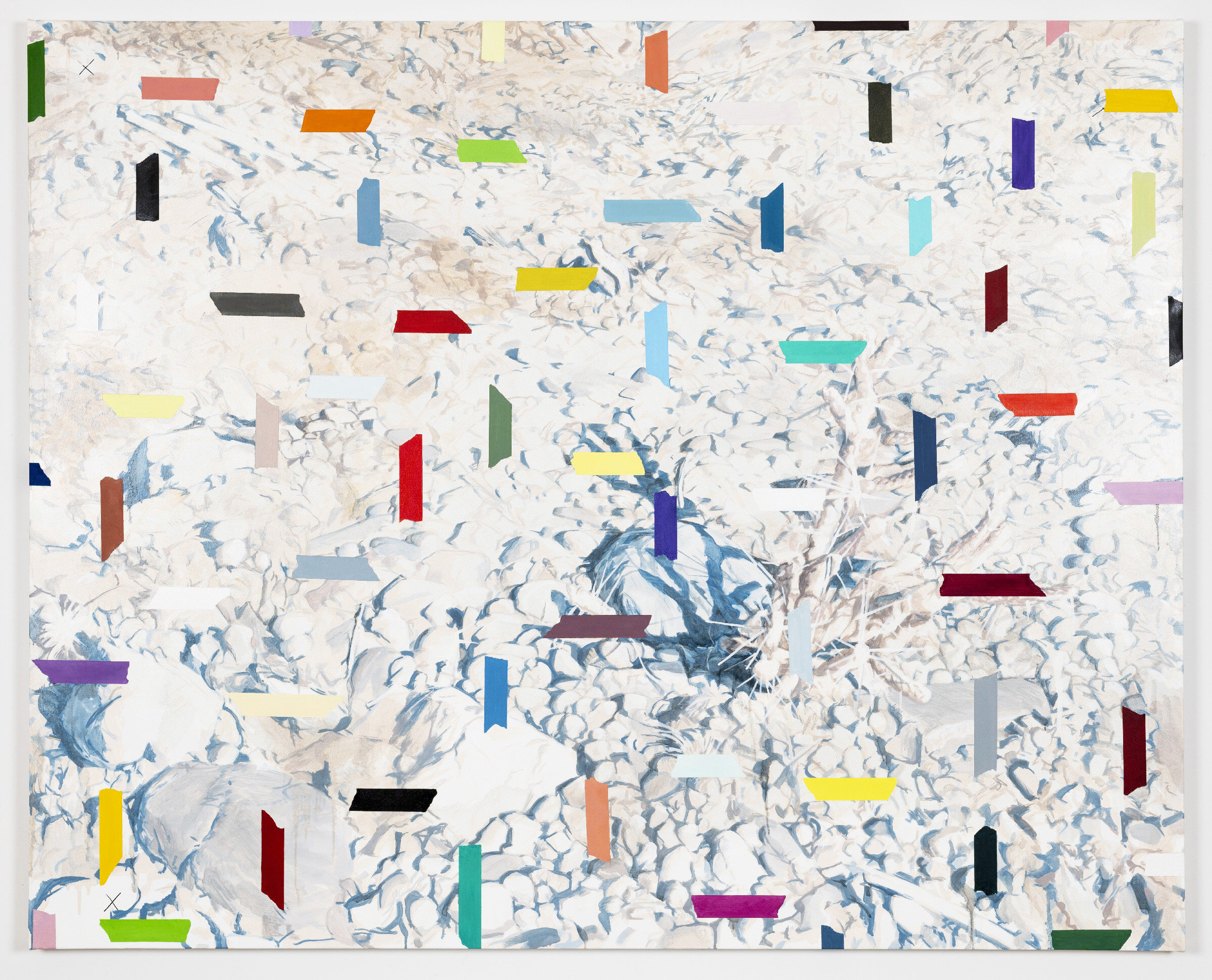

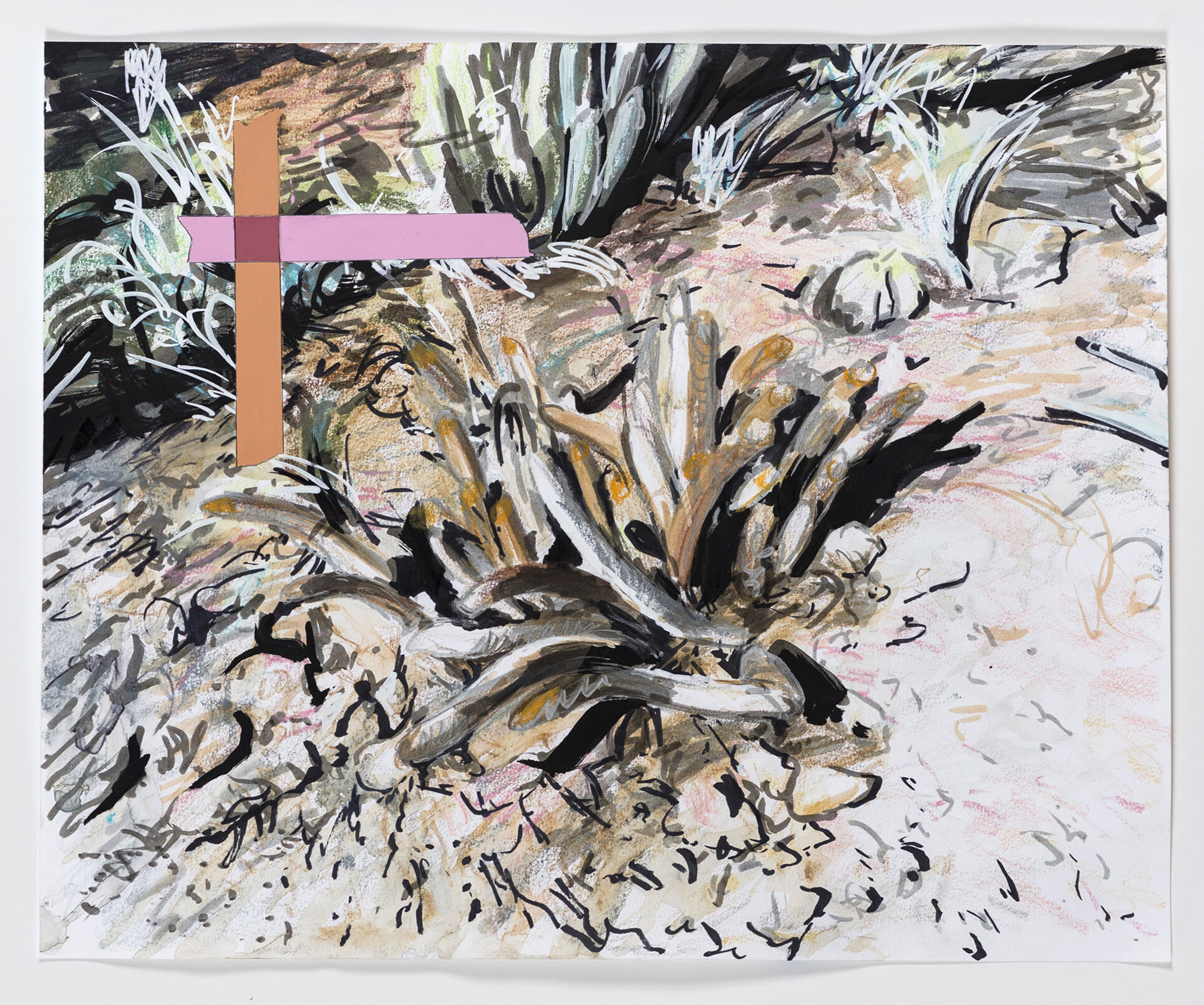

I began making the paintings in Rocks and Tapes in the wake of a series of exhibitions about nuclear weapons, my long-running motif for themes of apocalypse. These current works include oils on canvas and mixed media works on paper. The ecological imagery originates in photographs I take in the western deserts of the US. Some depict rockslides in which geologic features appear to be collapsing; others show landscapes tied to the testing and production of nuclear weapons, including the Hanford Site in Eastern Washington State near where I grew up. My paintings often incorporate swaths of white in reference to the intense, bleaching desert sun, and embedded in their surfaces are trompe l’oeil representations of slips of masking tape. The tapes allude to the practical tools and processes of my studio and to the omnipresence of technological intervention in our everyday lives.

The idea of painting masking tape came from a Sylvia Plimack Mangold painting I encountered at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo around the same time as my bike wreck. There’s a certain irony in presenting tape as a subject; it’s a banal material but essential for making all kinds of things. We use tape to affix things and to connect disparate objects. We also use it to mask out things or redact them. Representing tape in paint feels both entirely logical and utterly absurd. I render my tapes strips in various color schemes, sometimes allowing the primed canvas to show through. It’s difficult to say how I arrive at these systems; sometimes they refer to the depicted landscapes, but they also exist—as does our viewership of digital images—in a parallel universe of contextual frames, filters, icons, palettes and texts.

I’m writing this in the midst of the 2020 global pandemic. Currently, we seem to be struggling with a growing stack of crises that includes, in addition to COVID-19, a global economic meltdown, waves of social protests about racism and police brutality, a national leadership gap and the slow-moving planetary train wreck that is climate change. It can seem as though the world is falling apart.

This feeling of crisis is familiar to me from my bike wreck. I was challenged to stay alive in the face of various threats, precisely during a time when blood loss made it very hard to think clearly. The paintings in Rocks and Tapes, with their overlapping visual layers and fields of jagged rubble, embrace that sense of chaos. Taking an aerial vantage point, they are my attempt to gain perspective in a world of intensifying complexity. Like my pieces of tape, they’re about holding things together.